- Home

- About Us

- Sailing Courses

- Powerboat Courses

- SLC - Sailing License

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Instructors

- Practical Courses

- Fighting Childhood Cancer

- Free Courses Signup

- Gift a Sailing Course

- Sailing Opportunities

- Sailing Licenses and Certifications

- About the Sailing Certifications

- Sailing Blog & Helpful Articles

- NauticEd Podcast Series

- Yacht Charter Resources

- School Signup

- Instructor Signup

- Affiliate Signup

- Boat Sharing Software

- Sailing Industry Services

- Support & Contact

- Newsroom

- Privacy Policy

Weather Online Sailing Course

Smooth Sailing Ahead: Weather and Weather Planning

The Weather online course is an indispensable resource designed to empower sailors with the essential knowledge and skills needed to navigate weather and wind effectively. Crafted by weather expert Jay Brosius, this course stands out as the preeminent weather course for sailors.

Navigating through weather systems and understanding wind patterns are vital aspects of sailing, and this course provides a comprehensive overview of these critical topics. From decoding weather fronts to analyzing wind troughs, participants will gain a deep understanding of weather phenomena, enabling them to plan and execute sailing voyages confidently.

Whether you're a novice or an experienced sailor, this course is tailored to meet the needs of individuals at all skill levels. By enrolling in this course, sailors will enhance their ability to interpret weather forecasts and observations, ultimately becoming more competent sailors.

Estimated Time: 7 hours

Price: $39 (or $33 with the Captain Offshore Bundle of Courses)

The Weather online course teaches you the critical skills necessary to read, understand, and plan for the weather and wind as a sailor. This course, written by weather professional Jay Brosius, is the best weather course available for sailors.

Understanding weather and wind is a critical skill in sailing, and this course will teach you everything you need to know to plan your sailing voyages and vacations with confidence. From understanding weather systems and fronts to interpreting troughs and winds, this course will provide you with the skills and knowledge necessary to plan and navigate through weather patterns safely and efficiently.

Whether you are a beginner or an experienced sailor, this course is a must for anyone looking to improve their sailing skills and become knowledgeable and confident with weather forecasts and observations.. Enroll now and take the first step towards mastering the sailing art of planning for the wind and weather.

In this Weather Online Course you will learn:

- Northern and Southern Hemisphere Weather Theory

- What is a tropical wave

- What is a ridge, a trough

- How to read a 500mb weather map

- When to worry and when not to (ignorance is not bliss)

- How to predict impending weather conditions

- Cold Fronts, warm fronts, wind directions, wind changes

- Almost everything about the weather that you didn't even know to ask

We guarantee both your satisfaction AND Lifetime access to any sailing course you buy from us

More about this Weather Sailing Course

-

Learn sailing weather concepts, resources, and strategies for sailing and planning voyages

- View an excerpt from the Weather Course

- Extensive and essential knowledge for understanding the weather

- This Sailing Course takes approximately 7 hours of total time to complete

- Take as long as you need to complete

- Return as many times as you like to review

- Take the online test as many times as you like

- Adds the Weather Endorsement to your Sailing Certificate

This is an ONLINE course and tests viewable in your browser window.

Today's Investment: $39 (Or $33 with the Captain Offshore Sailing bundle of sailing courses)

Not convinced yet that online sailing courses are cool? Visit our fully interactive and completely free Basic Sail Trim Sailing Course. You'll see why online e-learning is SO MUCH BETTER than a boring old Book.

Weather is a technical topic that we tend to dismiss all too often. The trouble with dismissal is that it's our lives that are at stake. Author, John Brosius, puts it all into perspective for us. John is a respected weather consultant for weather prediction. In fact, John not only knows and explains the theory, but he wrote this comprehensive and easy-to-understand course while sailing his sailboat in the Pacific Ocean dodging tropical waves and depressions. Numerous emails were exchanged via satellite in the finalization of this weather course. It's one thing for a meteorologist to explain the weather but a meteorologist/sailor? - Now that's valuable!

Here, John has put about 7 hours of learning into a $39 extremely comprehensive NauticEd Weather Course for you. It's simply the best weather information you'll get regarding sailing. And NauticEd stands behind its money-back guarantee on all its learn to sail lessons. If you feel you didn't learn valuable weather information after completing this course then we'll happily refund your investment.

If you still have questions about NauticEd, the courses, and/or the sailing certifications, contact us via email or phone we're happy to help. Otherwise, register for the NauticEd Weather Clinic now!

If you've wanted to learn about and understand the weather, locally and globally batten down the hatches, pour a coffee, and get started right here. You'll gain an understanding of how to read a weather map, understand why the trade winds work in the directions that they do, and fully understand the aloof "Coriolis" force and how it makes the gas we live in spin in one direction in the northern hemisphere and the other in the southern.

Please enjoy our Weather Course.

By Jay Brosius

M.S., Weather Professional

Student Reviews

Michael K.

2024, 15 Oct. 21:57

A lot of information that can trigger my own reading on the details.

Jeff H.

2024, 11 Jun. 16:17

There was a lot of good information and images to assist with understanding

Nigel J.

2024, 08 Jun. 04:32

Hard

Gisle H.

2023, 14 Aug. 21:04

Important stuff for sailors

Terence H.

2023, 09 Mar. 18:19

I have always found weather to be difficult. Nothing about weather is intuitive for me. Much to my surprise I did notice that when I finished the whole course there were many things I retained. I was expecting to learn, regurgitate for the test and then quickly forget what I had learned. I think I actually retained some of the course content.

Steve E.

2023, 11 Feb. 15:51

Good info

Patrick H.

2023, 05 Feb. 01:39

I dont know too many people who will remember 60% of this. A whole lot of detail.

James L.

2023, 10 Jan. 20:09

It’s very difficult to get to grips with Weather as it is has many factors but this really advanced my knowledge

JOHN W.

2022, 17 Nov. 17:21

pleased the southern hemisphere is addressed

Amanda S.

2022, 18 Sep. 15:05

Good sound platform for understanding global weather.

Andrew Lucas (Luke) v.

2022, 15 Feb. 22:37

Very worthwhile course

Markus S.

2022, 19 Jan. 00:47

It gives in-depth information, but I find it too technical. I'd like to sail and not to get a master in meteorology.

- 1

- 2

List Price: $39.00

Excerpt from the course

Expand Excerpt from the course3.4 Fronts

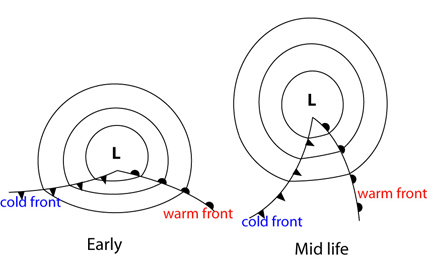

Now comes the important topic of weather fronts. A front is a boundary between two different air masses. Differing air masses will have different characteristics of one sort or another, such as different moisture content and temperatures. Remember the cool air mass in a valley at night, and its sharp boundary with adjacent warmer air? Now we are talking about cool and warm air masses that extend hundreds or thousands of miles.

As a consequence of the different air mass temperatures and different resulting air mass pressures at differing latitudes, and of the earth’s spin, adding a Coriolis Effect, the earth naturally has wind bands at various latitudes with rather distinct boundaries. We talked about these earlier.

We also talked about local and regional effects as some air warms more than others, gets lighter, lifts, other air moves in, and over larger areas, the winds start circulating.

If such a disturbance and lifting occurs along the boundary of two air masses, such as for example between two different wind bands on the earth, the inflowing air to replace the lifting air will circulate around the rising air due to our friend the Coriolis Effect. This circulation will circulate the colder air boundary toward the warmer side and the warmer air boundary toward the colder side.

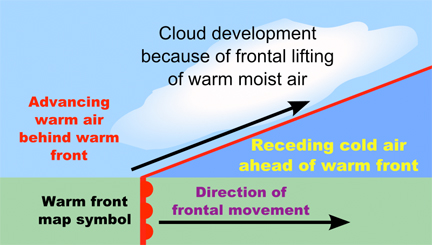

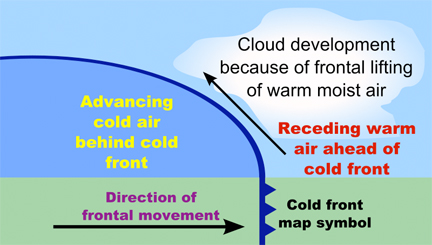

An advancing cool air mass boundary is called a cold front. An advancing warm air mass boundary is called a warm front. On a chart, a warm front is denoted by a line showing the position of the front with rounded filled semicircles on the advancing side of the front. A cold front is shown by a line showing the position of the front with filled triangles on the advancing side of the front. An occluded front alternates these symbols on the same side. A stationary front alternates symbols on alternate sides.

Notice that there is often a sharp shift in the direction of the isobars as they cross a front. This will also indicate a wind shift at that location, a common indicator of the passage of a front. While a change in airmass characteristics, such as moisture content (e.g. dew point, the temperature at which dew forms) is a better theoretical indicator of a frontal passage, the wind shift is the most important one to the mariner.

Once this circulation pattern is formed around an unstable disturbance, causing an area of low pressure in the center, if there is a means at a higher altitude to ventilate away the lifting air in the Low, the low will usually strengthen (deepen or lower in pressure). Once formed lows generally move eastward, being carried along by upper air currents flowing eastward.

However, sometimes some other factor, like a blocking stationary surface high-pressure area or a lack of upper-level steering currents, can prevent forward motion. Eastward to pole-eastward motion is the norm.

Speaking for the Northern Hemisphere, as cooler air moves south behind the low-pressure center, it pushes ahead the warmer air and will move under that air, lifting it. Now we have another mechanism for lifting air, the large-scale movement of cooler air under warmer air (or warmer air sliding up over cooler air). This occurs along the front, sometimes for a thousand miles or more. The lifting cools the air, and if any significant moisture is present in the lifted air, clouds usually result, often accompanied by rain.

The following figure illustrates a cross-section of typical warm and cold fronts. For both warm and cold fronts, the surface chart showing the fronts will show the position of the air mass boundaries on the surface of the earth. But it is important to realize that particularly in the case of the warm front, the warm airmass can extend for hundreds of miles ahead of this surface front at higher altitudes. Sometimes the effects of an approaching fast cold front can be seen a hundred miles or more in advance of the front.

Warm fronts slide easily up over cooler air masses, and the warm front air can lift to altitudes of over 30,000 feet (10,000 meters) as it does so. Again, the lifting of air is forced by this relative movement of air rather than by direct thermal heating effects, but many of the consequences of lifting air are the same. As the warmer air slides over the cooler air and lifts, eventually, the temperature will drop enough due to the lifting into lower-pressure upper air zones, that moisture will condense out causing clouds. However this process is usually stable, so the clouds that are formed tend to be flat layers rather than high-building clouds.

At these higher altitudes, the cloud formations will often tell of the approaching warm front up to a day or more before it arrives. Clouds start as high “cirrus”, often with curving tails (“mares tails”), and gradually thicken to a hazy layer of “altostratus, gradually turning opaque and darker as it lowers as the surface warm front approaches becoming “stratus” and finally often “nimbostratus” where the nimbo prefix denotes rain.

Cirrus Clouds |

Abbreviation |

Ci |

Altostratus Clouds |

Abbreviation Genus Altitude Classification Appearance Precipitation cloud? |

As Alto- (High) -stratus (layered) 2,000-5,000 m (8,000-20,000 ft) Family B (Medium-level) Sheet or layer, can usually see the sun through it Yes, large Areas of precipitation |

Stratus Clouds |

Abbreviation Genus Altitude Classification Appearance Precipitation cloud? |

St Stratus (layered) Below 2,000 m (Below 6,000 ft) Family C (Low-level) Horizontal layers Yes, but usually minor precipitation |

Nimbostratus Clouds  Nimbostratus Virga |

Abbreviation Genus Altitude Classification Appearance Precipitation cloud? |

Ns Nimbo- (rain) -stratus (layered) Altitude below 2,400 m (below 8,000 ft) Family C (Low-level) Dark, Widespread, formless layer Yes, but may be virga (falling streaks that vaporize before hitting the ground) |

Steady rain often eventually results before the surface warm front arrives. This rain usually eases off when the surface front passes, accompanied by somewhat warmer, more humid relatively hazy air.

Warm fronts represent the portion of air around a low that is moving away from the equator northward. These fronts extend to the east of the low center and move generally eastward and away from the equator.

Cold fronts represent the forward-moving boundary of cold air that is wrapping down toward the equator behind the Low, eventually wrapping around the Low. Cold fronts often move faster than warm fronts. While warm fronts often move at around 15 knots of speed, a cold front can move from 20 to 40 knots.

As a cold front approaches, it pushes the warmer air ahead of it and works its way under it. Whereas the cross-section of a warm front shows a gentle slope upward ahead of the front, a cold front usually has a steep slope, being steeper with faster speed. One of the reasons for this steepness is surface friction, which prevents the cold front from pushing a wedge of cold air well under the warmer air but being colder, the higher portions of the cold air will not move over the warmer air. In the case of the warm front, there is no friction to prevent the warm air from sliding easily over the cooler air. Sometimes a fast energetic cold front can appear as an approaching wall. Some dramatic footage has resulted when the colder air includes dust or smoke, making its approach very visible.

So cold fronts are much steeper than warm fronts, generating more rapid lifting. Along this front, the lifting of the warm moister air ahead of the front can generate very high cumulous clouds with thunderstorms, squalls, and heavy showers. After the front passes, the dryer cooler air behind it moves in, generally bringing clearer skies, better visibility, and scattered low fair-weather cumulous clouds.

Cumulonimbus Clouds |

Abbreviation Genus Altitude Classification Appearance Precipitation cloud? |

Cb |

|

|

Abbreviation Genus Altitude Classification Appearance Precipitation cloud? |

Cu Cumulus (heap) Base below 2,000 m (below 6,500 ft) (tops vary) Low-level (family C) or vertical (family D), depending on size Puffy Depends. Cumulus humilis and mediocris, most likely no, but congestus, sometimes yes. Cumulonimbus, yes, but may be virga. |

Note that the warm air is moving away from the equator and the cooler air is moving toward the equator. Since there is a sharp air mass boundary, there tends to be a rather sudden change in wind direction as one crosses the boundary, or equivalently as the boundary crosses your position, reflecting the differences in air mass movements. This difference exists in addition to the Coriolis Effect that tends to circulate air around a Low. Isobars will tend to bend more sharply at the front, reflecting the wind shift.

Consequently, for most of us sailing on the equator side of the Low, as a front passes, the wind tends to “veer” or shift in a clockwise direction rather suddenly. Winds in advance of a warm front tend to be from the Southeasterly direction, changing to Southwesterly as the warm front passes. As the following cold front passes the wind often shifts from Southwesterly to Northwesterly and increases. The barometric pressure will start to drop as the warm front approaches. Sometime after the warm front, the pressure will stop falling as the Low passes by, then begin rising. The rapidity of the drop in pressure is an indication of how tightly spaced the isobars are, and the depth of the lowest reading is an indication of the strength of the low, the power wound up in the low, and the potential accompanying storm.

Highest winds are often found associated with lows, particularly the powerful, deep lows that wind up tightly and have many closed-circle isobars around them.

A high-pressure area of cooler, dryer air often follows the low as the cool air trailing the low fills in. This tends to be a relatively broad dome of higher pressure with winds circulating around it and often bespeaks fair weather. The center of the High usually has light and variable winds with steadier mild to moderate winds further way circulating around it, unlike the Low with its typical stronger winds near the center, particularly in winter.

However, there are circumstances when a High can have high winds, such as when it has high convex curvature or pushes up against a low compressing the isobars between them into a “squash zone”. Therefore, while increasing winds are often associated with a falling barometer, it is possible to see high winds without a falling barometer, in which case you are likely in such a squash zone moving parallel to the isobars.

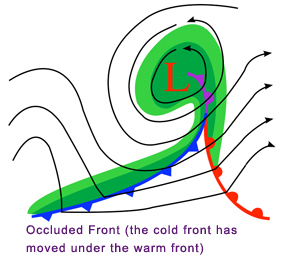

Since cold fronts move faster than warm fronts, a cold front will in the normal evolution of a Low overtake the warm front and begin moving under the advancing warm air to create a situation where the warm front is lifted off the surface. This is an “Occluded Front”. This is a mature stage of a Low, and at this stage, the Low-pressure center will usually start to fill in and degenerate. There is usually however still a large amount of condensing moisture aloft in the warmer lifting air, often falling as precipitation of one form or another.

Stratocumulus Clouds

When warm, moist air is mixed with drier, cooler air and the mixture is moving beneath warmer, lighter air above, clouds will often form as rolls or waves. Sometimes, especially in summer, there are gaps through which the Sun can shine. This cloud is called stratocumulus, meaning sheets of lumpy cloud. Stratocumulus is grey, white, or a mixture of both, usually with some darker patches. It is a low-level cloud that can look threatening, but unless it is very thick usually only drizzle or light precipitation falls from it. It can also form in air forced to rise over hills. Its base is typically at 1,000-7,000 ft (300-2,000 m). Although stratocumulus is not usually a badweather cloud, its presence may indicate that worse weather is on its way, or is just clearing.

In the temperate parts of the world, the surface isobar chart will show a lot of closed circles around highs and lows. Some isobars further away from the highs and lows may not be closed, but more linear. A look at the surface isobar chart can give a quick picture of the weather, and since most Lows travel in an Easterly direction, you can get an idea of how weather is likely to progress. Highs bespeak generally good clear weather. The direction of the isobars will tell you wind direction, and the spacing of the isobars adjusted for curvature will indicate wind speed. Look to see if there are pending collisions between highs and lows (e.g. a high that won’t get out of the way of a Low), or lows that come together. Both strongly suggest more severe weather in the offing.

Wind speeds will also vary with latitude. Close isobars create stronger winds nearer the equator than they do further from it.

The following is a real weather map of the Pacific taken on September 27 2024 taken from https://www.weather.gov/forecastmaps/. Note cold, warm, stationary, and occulted fronts, highs, lows, areas of convergence and the remnants of Hurricane Helene.

>>>>>>>>>>>

Want to learn more and be NauticEd certified in weather, go places faster and in more comfort - and perhaps save your life/crew/boat? Register now!

Other sailing courses that you might enjoy

Sea talk testimonials

As a professional power boat captain and boating instructor, I was impressed with the level of detailed content and practical teaching information covered in the series of NauticEd courses